STATE of NORTH CAROLINA in the GENERAL COURT of JUSTICE

COUNTY of PITT DISTRICT COURT DIVISION

STATE of NORTH CAROLINA

(plaintiff)

v.

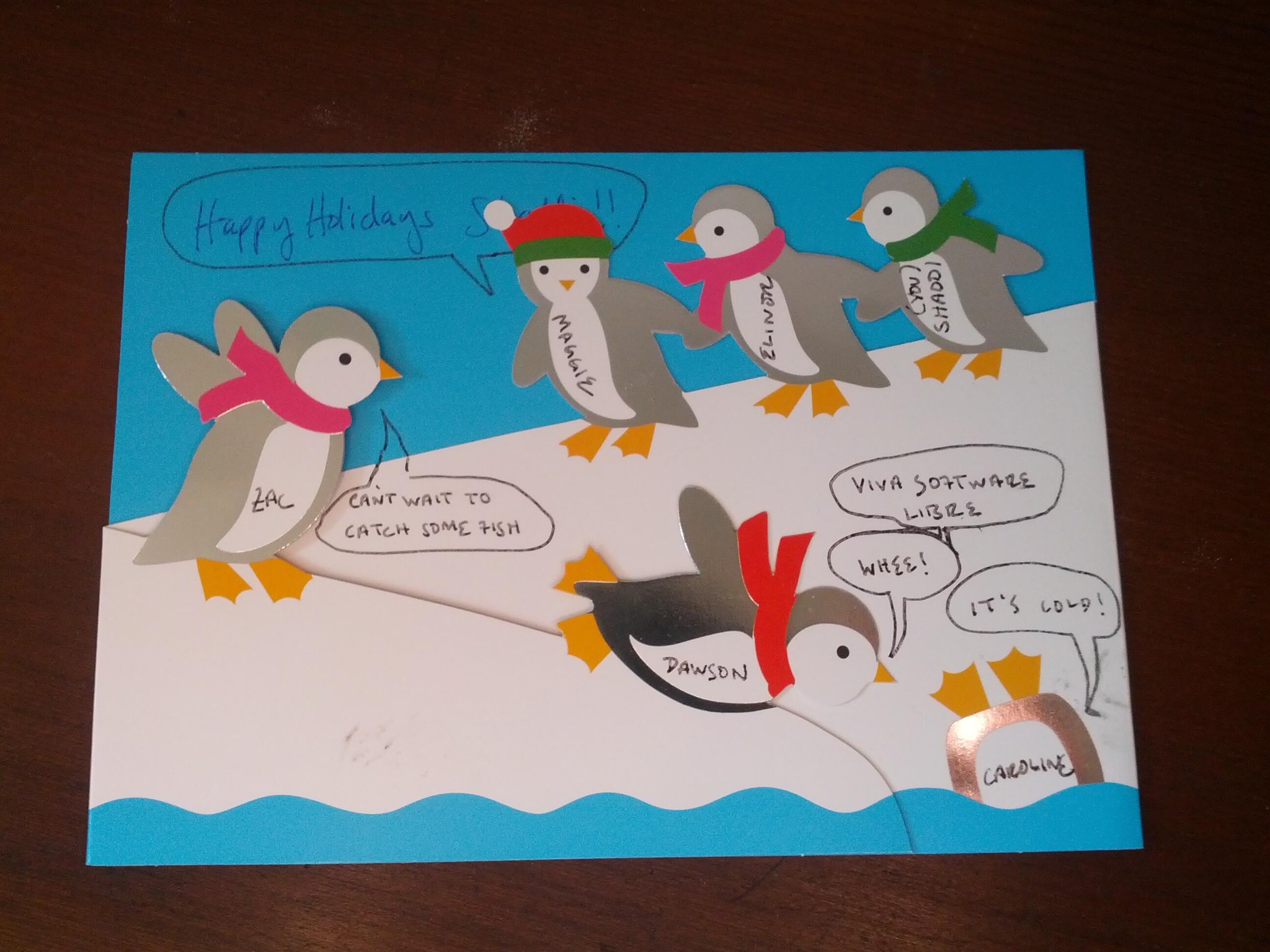

WILLIAM DAWSON GAGE

defendant

“Since multiplicity of comments, as well as of laws, have great inconveniencies, and serve only to obscure and perplex, all manner of comments and expositions on any part of these fundamental constitutions, or on any part of the common or statute laws of Carolina, are absolutely prohibited.”

—John Locke, “The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina”, 1 March 1669

HERE NOW COMES the defendant, William Dawson Gage, by and through his counsel Mr. Alexander Paschall, and otherwise in his own voice and person as author of this motion, with the purpose to move this Court to DISMISS the case in question. The grounds for this “MOTION to DISMISS” are found in NCGS 15A-954(a), and in the several canonical provisions of constitutional and international law referenced below. In support of this motion, defendant Mr. Gage would show as follows:

1) That speech and writing in the context of human interpersonal relations are protected by state and federal constitutions and by international law, and that the use of language for communication, correspondence, and expression in the realms of friendship, courtship, and societal intercourse generally cannot be rendered criminal by an Act of the North Carolina General Assembly or an Order of the District Court.

2) That per NCGS 15A-954(a)(1) there are grounds for dismissal in that the statute (NCGS 14-277.3A, known in North Carolina as “the stalking law”) is unconstitutional on its face, the text admitting of no other interpretation than that the enactment was carefully and purposefully constructed to empower the agents of State government to violate constitutional rights.

3) That the “facial unconstitutionality” of NCGS 14-277.3A may be readily detected and inferred from the inclusion of a unique “prefatory passage” concerning the “legislative intent” of the General Assembly (circa 2008). In this section we find the unconstitutional purpose of the statute more-or-less openly declared.

4) That the express sense of the declaration of “legislative intent” in NCGS 14-277.3A violates Article I, Sec. 6 of the Constitution of North Carolina, insofar as it is clear that the phrases “…to encourage effective intervention by the criminal justice system…” and “…to enact a stalking statute that permits the criminal justice system…” are meant to countenance undisguised transgressions of the “separation of powers doctrine”. The very language of “criminal justice system” is indicative of the post-constitutional mentality which has infected both lawyers and lawmakers in North Carolina, and its meaning should be understood in terms of “non-separated” or “integrated” governmental powers in the context of the criminal law.

5) That furthermore NCGS 14-277.3A is unconstitutional on its face in light of Amendment I to the Constitution of the United States insofar as the statutory definition of “harassment” in 14-277.3A(b)(2) has no other purpose than to empower the integrated and predatory State government to violate the closely-related freedoms of speech, press, association, assembly, and religious and political conscience. The hysterically over-broad and hypersensitive language in said definition1 has the obvious purpose to target every conceivable method and mode of expression.

6) That upon the same (or very similar) reasoning as the above-given argument with respect to Amendment I, NCGS 14-277.3A is likewise in plain violation of Article I, Secs. 12, 13, and 14 of the Constitution of North Carolina, which concern (respectively) the kindred liberties of “assembly”, “worship/conscience”, and “speech/press”, all of which the statute presumes to restrain, regulate, and deter.

7) That NCGS 14-277.3A is furthermore also unconstitutional on its face according to the “due process clause” of Amendment XIV to the Constitution of the United States, inasmuch as its machinery of ambiguous and expansive definitions, problematic terms, and unnatural constructions presents an all-but-insuperable barrier to making a successful defense in the trial court; the same inherently confusing and biased terms are likewise practically unintelligible and nonsensical in the hands of a District Court Judge or a jury of 12, which results in an almost-total denial of “due process of law”. One cannot escape the conclusion that the General Assembly intended to enact just such an unconstitutional statute whose purpose—full stop—is to “deprive of…liberty [and] property”, or in the words of the legislator, “to hold stalkers accountable for a wide range of acts, communications, and conduct.” This notion of a “criminal justice system” which “holds stalkers accountable” is a tell-tale sign of this offensive yet commonplace attitude of disdain and contempt for the “due process of law” as such.2

8) That NCGS 14-277.3A is likewise unconstitutional on its face according to the “equal protection clause” of Amendment XIV to the Constitution of the United States (echoed/mirrored in NC Constitution Article I, Sec. 19). This dimension of unconstitutionality in fact involves the awkward but necessary concept of “an unconstitutional constitutional amendment”, namely the so-called “Victim’s Rights Amendment”. The statement of “legislative intent”3 in 14-277.3A bears a striking resemblance to the language in the “victim’s rights amendment”4, and it is fair to say that they both sanction a vision of North Carolina law where the principle of “equal protection” is done away with altogether, to be replaced by the aggressively punitive and draconian “criminal justice system”, whose mission is “accountability” for the accused and “dignity” and “respect” for the accusers.

9) That moreover the express “legislative intent” of NCGS 14-277.3A involves a shameless disregard for the the constitutional doctrine of the “sovereignty of the people” found in NC Constitution Article I, Sec. 2; the purpose of the statute is the violent regulation and surveillance of the entire society, the singling out of certain non-conformist or maladjusted individuals as “stalkers” (as “criminals” that is, even as “felons”), and all on behalf of a relatively privileged class of “victims” whose interests are to be understood in terms of “personal privacy”, “autonomy”, “quality of life”, “security”, and “safety”. This represents a clear departure from the fundamental precept of the criminal law which is the difference between right and wrong actions. Dispensing with such old-fashioned ideas as “morality” and “society”, NCGS 14-277.3A presumes to institute a form of government where the “will of the people” is abandoned, and “political power” is exercised not “for the good of the whole”, but “for the advantage of some over others”. Thus is the statute facially unconstitutional according to Article I, Sec. 2.

10) That likewise is NCGS 14-277.3A facially unconstitutional according to NC Constitution Article I, Sec. 20 which prohibits “general warrants” for the arrest of persons. The State’s pleadings in the instant case, as well as in previous cases against the defendant Mr. Gage pursuant to the “stalking law”, do not “particularly describe” the allegedly offending conduct, but rather give an obscure and abbreviated reference to the statutory language of 14-277.3A and a fragment of description which does not, on its face, describe an offense under criminal law. This is a pervasive problem with “stalking warrants” in North Carolina, wherein defendants frequently “have no idea what they were charged for”, a phenomenon which suggests that such warrants are indeed unconstitutional “general warrants” in violation of Article I, Sec. 20.

11) That in addition to the several dimensions of “facial unconstitutionality” rehearsed above, that there are also grounds for dismissal per NCGS 15A-954(a)(1) in that “as-applied” to the defendant William Dawson Gage and to “victim” Caroline Morgan Fryar the statute violates Article I, Sec. 16 of the Constitution of North Carolina. The “course of conduct” or “sequence of occasions” which constitute the history of “interaction” or “relationship” between the two parties traces back to their meeting circa 2007 as undergraduates at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, quite certainly prior to the enactment of the “stalking law”. This is to say that NCGS 14-277.3A was passed after the “defendant” and “victim” had met one another, and that to apply the statute to them violates the constitutional prohibition against “ex post facto laws”.

12) That there are furthermore good grounds for the dismissal of the proceedings per NCGS 15A-954(a)(8) in that the court lacks jurisdiction over the subject-matter of the written-word sent through United States Mail; if there were to be an alleged violation of criminal law in said writings, the jurisdiction would nevertheless be federal in nature. The “letters” which supposedly constituted the offense of “stalking” were transported in the custody of the United States Postal Service by federal employees via federal property. The envelopes were “stamped” with authorized USPS postage. The mailing address for the “Farmville Public Library” was obtained by defendant using a “federal website” operated by the US Department of Labor which was available to him in the Orange County Detention Facility. The mail was inspected and read by officers of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office who did not find anything suspicious or illegal about the materials, and who carried each of the three “letters” to the US Post Office in Hillsborough. For this and other reasons the State of North Carolina and the General Court of Justice and (especially) the Farmville Police Department lack criminal jurisdiction over these acts of free expression which were unambiguously federal in nature.

13) That the accepted understanding of the term “the law of the land” in NC Constitution Article I, Sec. 19 relates to that “supreme law of the land” which is established in the Constitution of the United States, and that these United States were a signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and are generally subject to international law as set forth in that and other documents.

14) That the civil and criminal proceedings against him in the Courts of North Carolina have violated defendant Dawson Gage’s fundamental human rights under international law as embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

15) That the criminalization of defendant Mr. Gage’s written correspondence violates Article 12 of the Universal Declaration which says that: “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation.”

16) That the criminal proceedings against defendant Mr. Gage, including the case here in question, have the purpose of oppressing and demeaning him in his exercise of his civil and religious liberty to the freedoms of thought, worship, and conscience. Thus do the proceedings violate defendant’s rights per Article 18 of the Universal Declaration, which holds that “Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.”

17) That independently of his challenges to the lawfulness of these proceedings per state and federal constitutions, defendant Mr. Gage’s written correspondence was furthermore rightful and privileged under international law as provided in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration, where it is written that: “Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.”

18) That the “Charter of the Province of Carolina” granted by King Charles II in 1663, which was the original instrument of sovereignty establishing the Courts and the Laws of North Carolina, holds that “Provided nevertheless, that the said laws be consonant to reason, and as near as may be conveniently, agreeable to the laws and customs of this our kingdom of England”. Accordingly, defendant Mr. Gage would dispute and reject the lawfulness of “stalking proceedings” generally insofar as the statute and its tortured implementations are NOT “consonant to reason”, and inasmuch as the idea of human nature and action which is embodied in North Carolina’s “stalking law” is “disagreeable to the laws and customs of…England”.

19) That one especially clear deviation from “the laws and customs of…England” in this case pertains to the 38th clause of the Great Charter of 1215, which reads “In future no official shall place a man on trial upon his own unsupported statement, without producing credible witnesses to the truth of it.” The charges against defendant Dawson Gage in Pitt County were instigated upon the “unsupported statement” of certain officers Tetterton and Hawkins of the Farmville Police Department. It is necessary to understand that the “victim” Dr. Caroline Fryar did not receive the supposedly-offending “letters” sent to the Farmville Public Library, and did not play any discernible part in the procuring of the “warrants” by these “law enforcement officers”. In any event there was and remains a conspicuous lack of “credible witnesses”, which leaves only the unreliable “unsupported statements” of the officers, thus violating the letter and spirit of Magna Carta.

20) That there is also a plain departure from that “law of the land” which is Magna Carta with respect to the charter’s 45th clause, which says that “We will appoint as justices, constables, sheriffs, or other officials, only men that know the law of the realm and are minded to keep it well.”

21) That defendant William Dawson Gage is no more guilty of the “crime” of “stalking” than he is of the offenses of “terrorism”, “blasphemy”, “sedition”, “espionage”, or “witchcraft”.

Representing and arguing thus, defendant Mr. Gage would move for such orders as the Court may deem rightful and appropriate, including:

I) An order to dismiss the case in question.

=========================================================================

Respectfully submitted this day of 2 January 2023.

William Dawson Gage | defendant

513 Orange Street

Wilmington, NC 28401-4609

dawson@orangestreetlawschool.org

910-322-5853 X_____________________________

Alexander Paschall | counsel for defendant

Office of the Public Defender

P. O. Box 8047

Greenville, NC 27835-8047

P: 252-695-7300

F: 252-695-7192 X_____________________________

1“…written or printed communication or transmission, pager messages or transmissions, answering machine or voicemail messages or transmissions, and electronic mail messages or other computerized or electronic transmissions.”

2 “It is a basic principle of due process that an enactment is void for vagueness if its prohibitions are not clearly defined. Vague laws offend several important values. First, because we assume that man is free to steer between lawful and unlawful conduct, we insist that laws give the person of ordinary intelligence a reasonable opportunity to know what is prohibited, so that he may act accordingly. Vague laws may trap the innocent by not providing fair warning. Second, if arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement is to be prevented, laws must provide explicit standards for those who apply them. A vague law impermissibly delegates basic policy matters to policemen, judges, and juries for resolution on an ad hoc and subjective basis, with the attendant dangers of arbitrary and discriminatory application. Third, but related, where a vague statute “abut[s] upon sensitive areas of basic First Amendment freedoms,” it “operates to inhibit the exercise of [those] freedoms.” Uncertain meanings inevitably lead citizens to “steer far wider of the unlawful zone’ . . . than if the boundaries of the forbidden areas were clearly marked.” —”Grayned v. City of Rockford” (S. Ct. 1972)

3NCGS 14-277.3A(a) reads in part: “…Stalking involves severe intrusions on the victim’s personal privacy and autonomy. It is a crime that causes a long-lasting impact on the victim’s quality of life and creates risks to the security and safety of the victim and others, even in the absence of express threats of physical harm.”

4NC Constitution Article I, Sec. 37 reads in part: “Victims of crime or acts of delinquency shall be treated with dignity and respect by the criminal justice system.”